I: Geodata acquisition

Geodata acquisition includes all methods of data acquisition: from surveying methods (Resnik & Bill, 2018) to empirical surveys in geomarketing, e.g. by means of surveys. A comprehensive overview can be found in Bill, 2016, Chapter 5.

In addition to the maps mentioned in the introduction, aerial and satellite imagery and the remote sensing methods used to evaluate them (Albertz, 2001, see Chapter 5 in Bill, 2016) are of particular importance for obtaining up-to-date spatial data. Remote sensing in particular, today from satellite images to aerial images to spontaneous aerial surveys using UAS (Unmanned Aerial Systems), is proving to be very efficient, as it provides direct digital forms and neighbourhood relationships (i.e. geometry and topology) of objects such as forests, settlements or water bodies as typical land cover, as well as thematic information through evaluations of the spectral information using indices, classifications, etc. While satellite and aerial photo evaluations represent established methods of geodata acquisition, the UAS have been on everyone's lips recently. Camera systems carried on board of small unmanned aerial vehicles allow the acquisition of large quantities of images in a very short time, which very precisely lead to standard products such as digital surface models (DSM), DTMs, digital orthophotos or point clouds by means of photogrammetric methods (UAS photogrammetry, cf. Grenzdörffer & Bill, 2013).

In many cases, maps have to be converted into digital form by means of manual digitisation and compiled into spatially significant objects using information from card indexes, archives, etc.

In recent years in particular, a large number of new recording methods have been introduced. Laser scanning is mentioned here as an extremely powerful method, whether from an aircraft (Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS)), a mobile vehicle (Mobile Laser Scanning (MLS)) or terrestrial (Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS)). The huge number of points in a point cloud can be processed partly with automatic or semi-automatic procedures to object geometries, e.g. the digital surface model or object parts in the road space.

The increasing miniaturization of sensor technology leads to continuously working geosensor networks with which a wide variety of environmental data can be recorded with high temporal resolution. Sensor development as well as general developments in information technology increasingly influence the possibilities of geodata acquisition, be it as a component of a global infrastructure (e.g. the Internet of Things (IoT)) or by means of smartphones equipped with a large number of sensors, with which anyone can acquire data today.

While surveying methods and digitizations lead to vector data, i.e. geometries such as points, lines and areas described by coordinates, image-based methods and scanning of maps provide so-called raster data, i.e. geometries stored in a uniform matrix scheme, which can be converted more or less automatically into vector data.

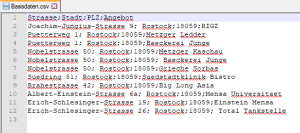

Factual data/thematic data, e.g. from surveys or official file systems, are either entered manually, read with document readers or originate from existing digital data collections, because more and more data collections already exist in digital form. If these factual data also contain indirect spatial reference forms such as addresses, geocoding enables their transfer into direct spatial reference forms such as coordinates. We will look at these processes in the exercise Geocoding.