Information processing in GIS

The generic term 'GIS' can be associated with various meanings:

- the underlying technology, i.e. the basic techniques from computer science coupled with methods specially developed in the fields of application,

- the projects initiated in the fields of application for the development and use of geodata, and

- the large number of products available on the market (see especially Bill, 2016, p. 144 ff., Harzer, 2017/2018).

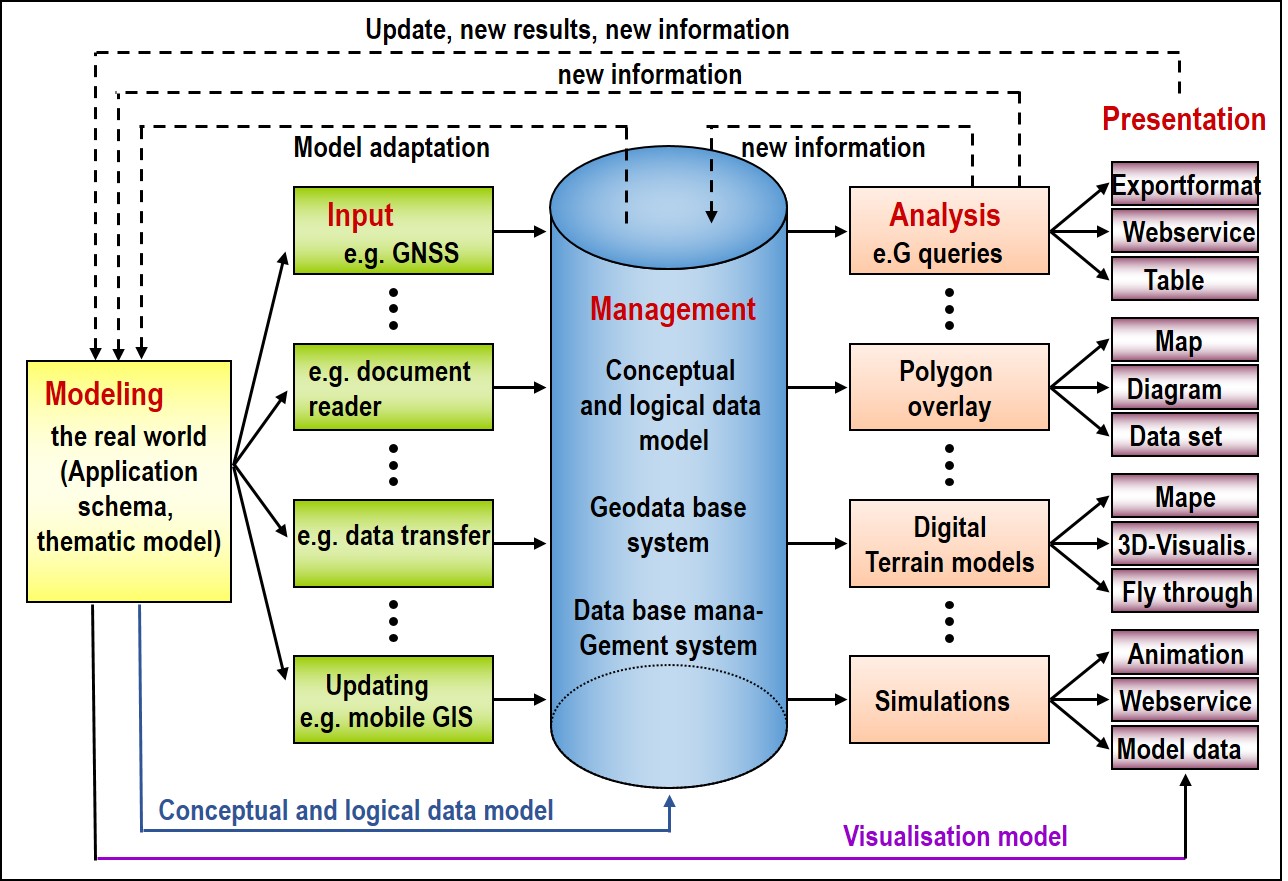

Focussing on the technology, a GIS must serve the entire functionality spectrum from data acquisition to data management and analysis to data presentation, classically referred to as the IMAP model of the GIS processing chain (Bill, 2016). It must therefore support a user in entering data into the system for his own and other relevant problems, in carrying out evaluations with this data and in being able to visualise or disseminate the results in a suitable form (analogue on paper, digital on the screen, on data media/storage media or accessible via the Internet using services, etc.). The complexity and interdependencies of these requirements are illustrated by the idealized processing chain shown below (see figure).

The processing chain usually starts with an application-specific and abstract modeling of a section of the real world in which the various object classes are defined that are necessary for processing certain tasks. This determines the thematic data model. The data are then to be collected, for which different collection methods are available. Existing data can also be transferred directly in digital form. The data must then be maintained and permanently updated.

The data is stored in (geo)database systems. This requires conceptual-logical modeling, i.e. data structuring in a form that the database system can process. In today's (object-)relational databases, the basic structure is the table, i.e. the data - geometry, topology, dynamics as well as factual data - must be converted into a tabular structure. It may also be necessary to adapt the original conceptual data model, which can lead to iterative processes and generally shows that a data model is not static, but must be permanently adapted to the changing framework conditions. Today's systems and data models take this circumstance into account by enabling the extension or profiling of existing data models. This makes it easier to transfer legacy data to newly developed applications. Special transformation tools help here with the data transfer. Applications usually process and evaluate data. In this way, the queries outlined in the examples above can be made to the dataset. However, more complex GIS analysis functions such as polygon overlay, shortest path analyses or simulations, e.g. based on noise propagation models, can also be calculated. The results of such analyses can lead to extensions of the model of the real world and be stored as new information, or even only temporarily examined and visualized in a tabular or graphical form. Of course, thematic cartographic forms of representation are particularly suitable for this purpose, for which representation models and rules must be set up and observed. These visualizations can also contribute to the extension of our mental model of the real world and thus flow back into the cycle of the GIS processing chain. Such iterative-recursive processes and cycles require a high flexibility of the geo-information system. In the following section, the four basic functional components of a GIS will be examined in more detail.

The IMAP processing chain in a GIS